Be sure to read the lesson adaptation for the Primary Classroom at the end of this blog!

Over the past two years, our district has put an emphasis on helping teachers and students focus on their emotional health in addition to their intellectual growth. Much time and energy has been spent on helping both educators and students recognize and name their emotions. At the same time, teachers and students are learning how to successfully manage these emotions.

Many students find writing to be a positive tool for recognizing and acknowledging their emotions. Planning specific lessons which provide students an opportunity to reflect on their emotions is a powerful experience for all.

With this in mind, we began the year with the poem ”Keep a Poem in Your Pocket” by Beatrice Schenk de Regniers. http://home.nyc.gov/html/misc/html/poem/poem1b.html This classic poem describes a child keeping a poem and a picture in their pocket to help them when they are feeling lonely at night when they are in bed. After reading the poem, students made an origami pocket and described a significant object they would keep in the pocket. The writing provided students a safe place to express their feelings and share something personally important to them. origami.lovetoknow.com/about-origami/how-make-paper-pocket

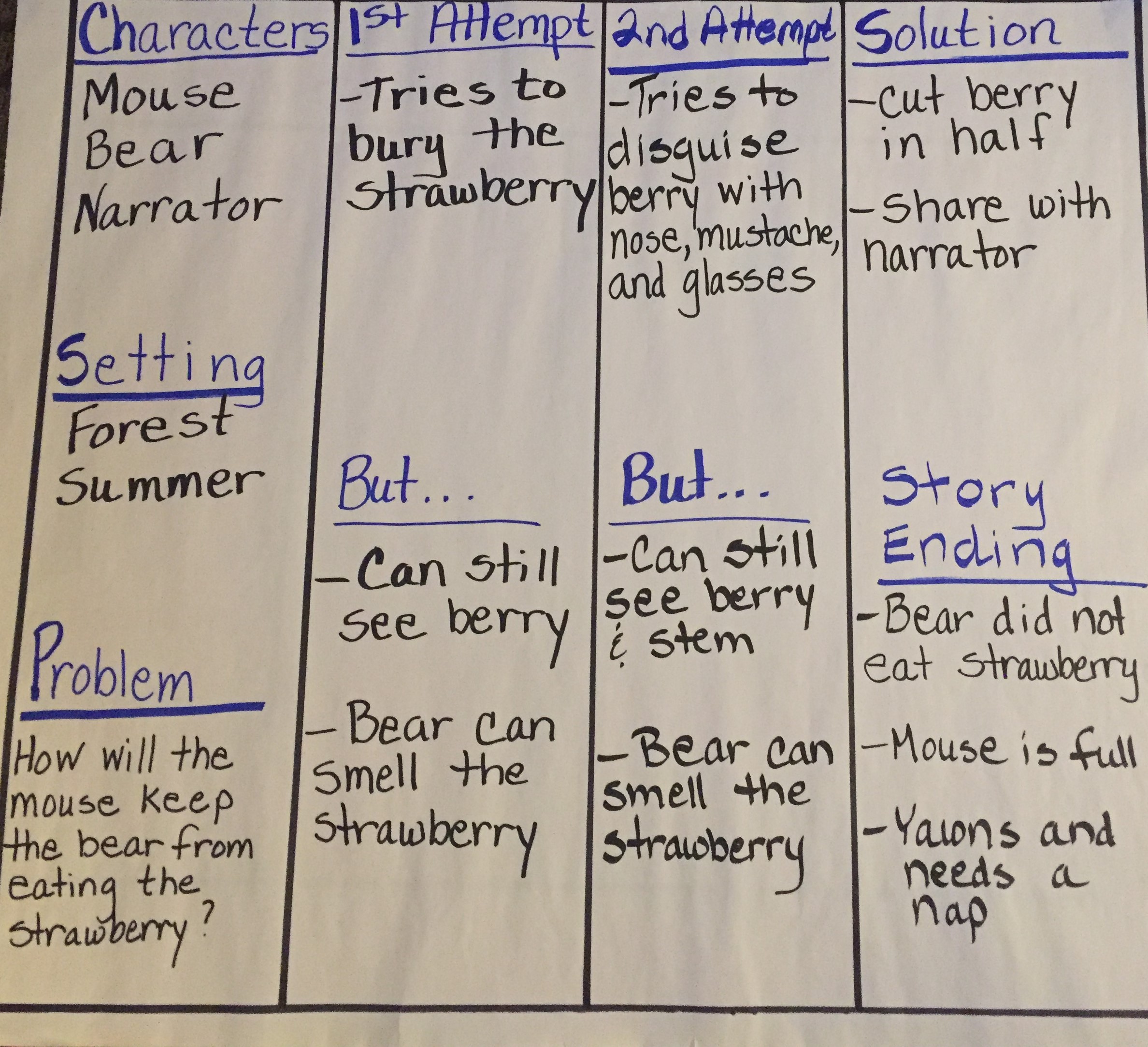

As our school year came to a close, we visited the theme of things that have personal importance to us again. The focus this time was a Special Place. We began with reading picture books on special places, including All the Places to Love by Patricia MacLachlan www.amazon.com/All-Places-Love-Patricia-MacLachlan/dp/0060210982 , Owl Moon by Jane Yolen www.amazon.com/Owl-Moon-Jane-Yolen/dp/0399214577 , Peek-a-Boo by Allan Ahlberg www.amazon.com/s/ref=nb_sb_noss?url=search-alias%3Dstripbooks&field-keywords=peek-a-book+book+by+ahlberg&rh=n%3A283155%2Ck%3Apeek-a-book+book+by+ahlberg and Up North At the Cabin by Marsha Wilson Chall www.amazon.com/s/ref=nb_sb_ss_i_2_9?url=search-alias%3Dstripbooks&field-keywords=up+north+at+the+cabin+by+marsha+wilson+chall&sprefix=up+north+%2Cstripbooks%2C186&crid=109CNK231UQDH&rh=n%3A283155%2Ck%3Aup+north+at+the+cabin+by+marsha+wilson+chall .

Each of these authors focus on special everyday places, using vivid details and descriptive word choices to help the reader experience the importance the place has for the characters.

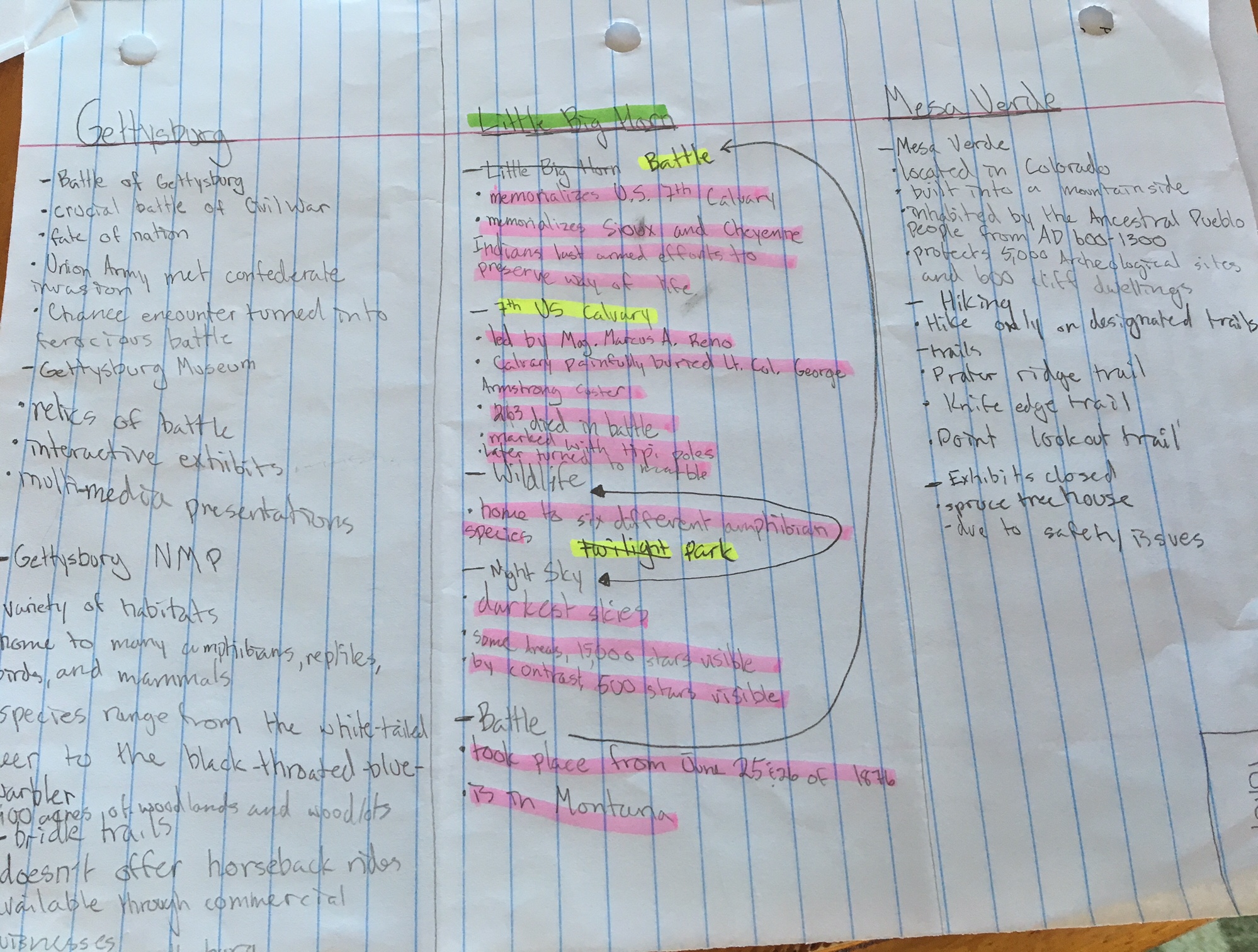

To begin, students brainstormed places which were significant to them. After a minute of brainstorming, students chose one place from their list. To better focus their writing, the chosen places needed to be specific. For example, California is a broad place, but the beach is a more specific place. I encouraged the students to think about an everyday location, although they could make any choice they wanted.

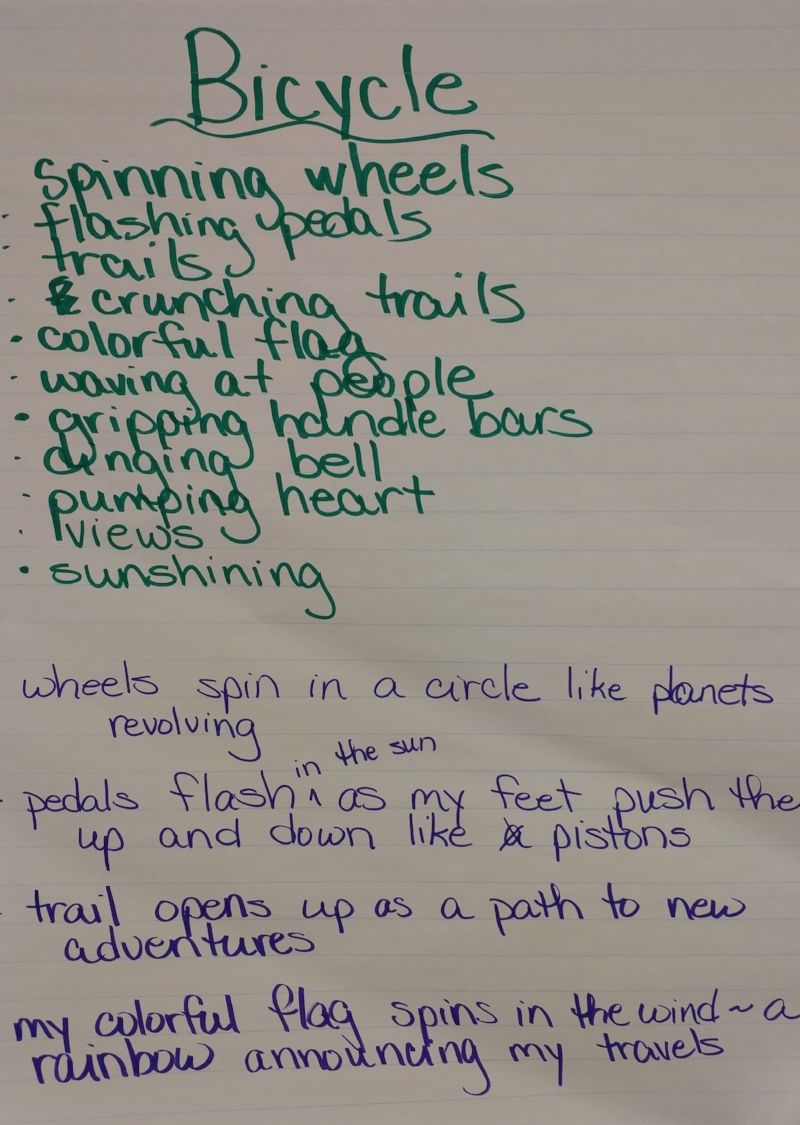

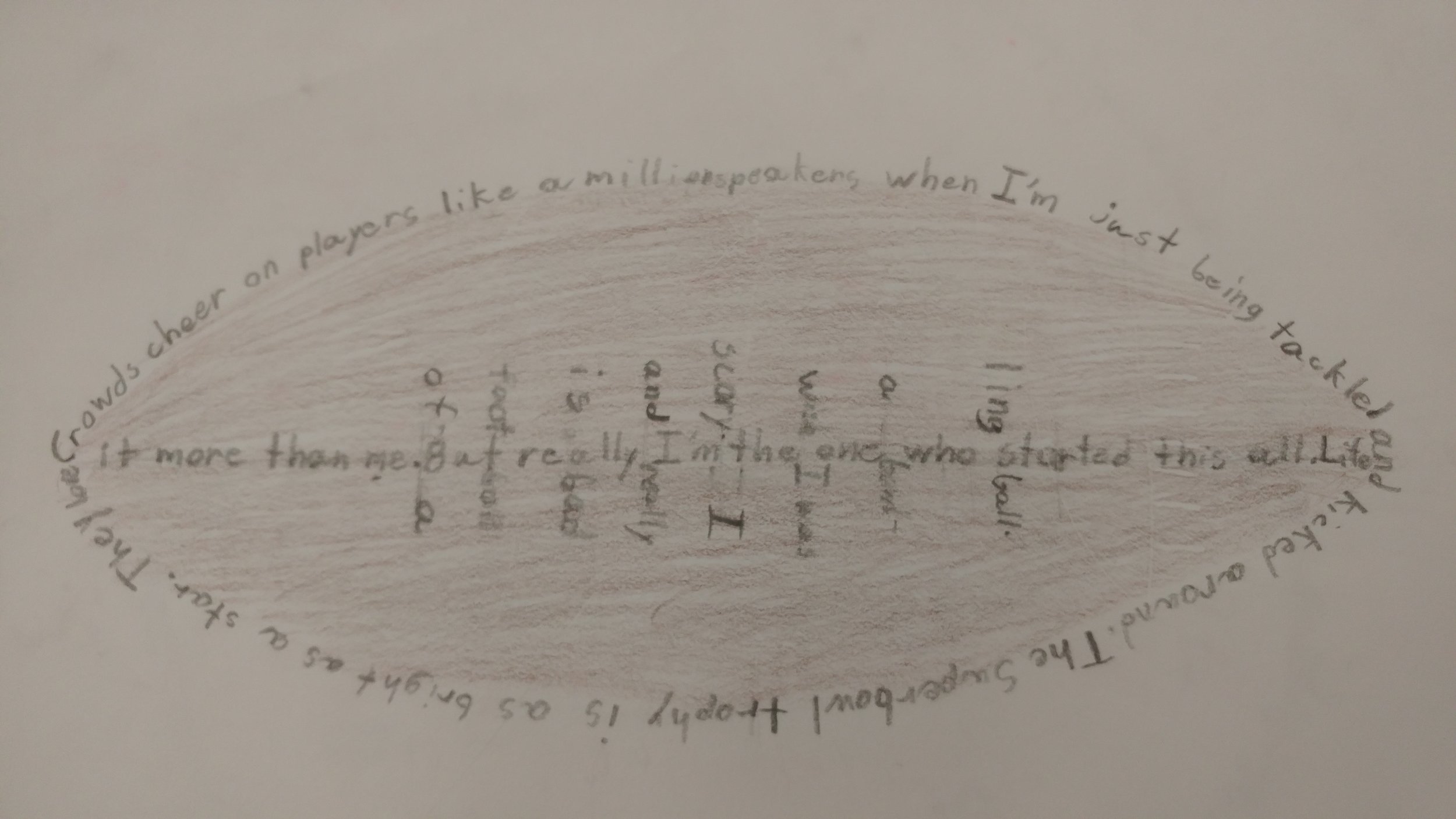

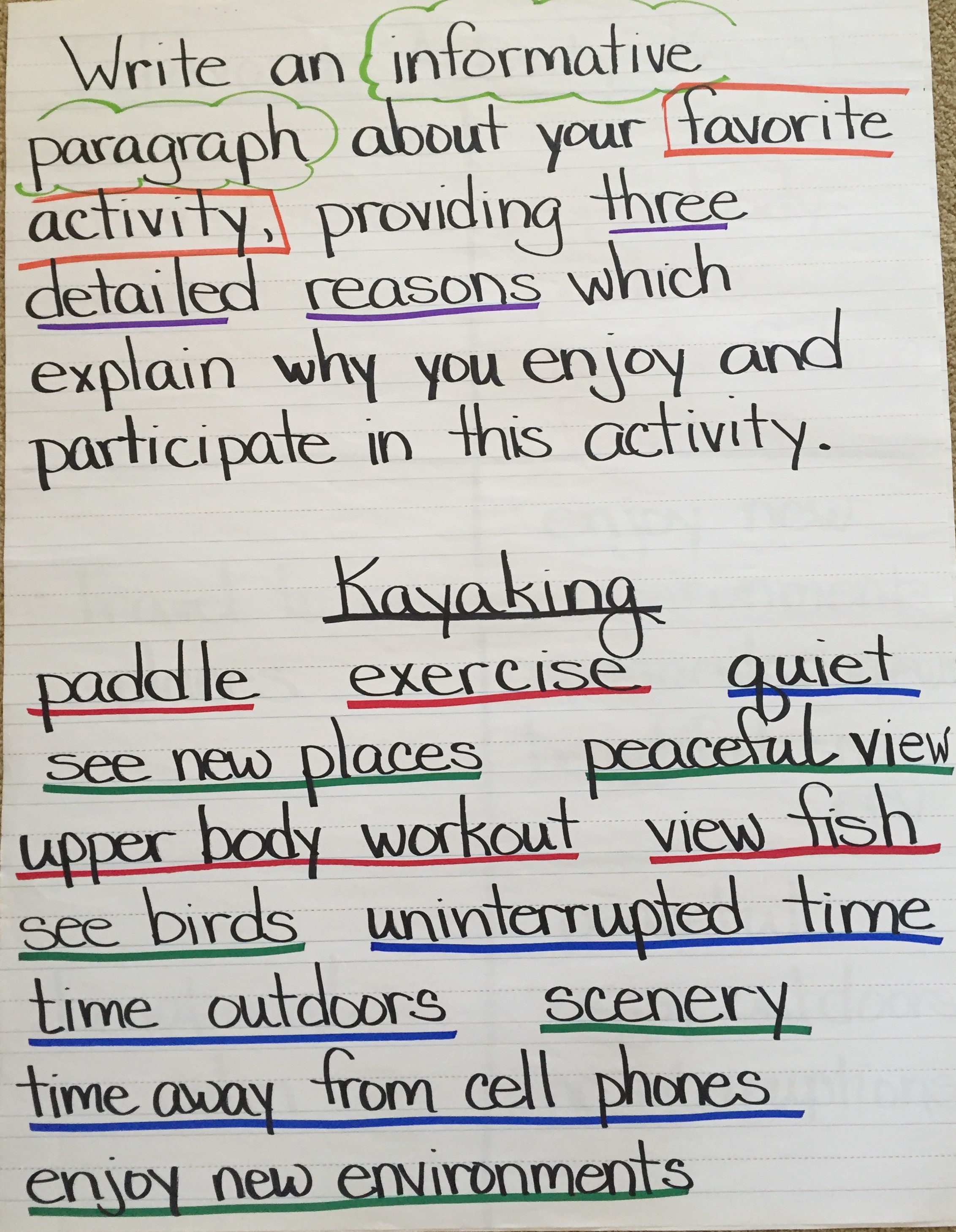

Next, students brainstormed activities they did in this place. By focusing on what they did at their place, the students’ writing became more than a list of locations. After brainstorming this list, they chose three activities that would be interesting to the reader.

As we had read the mentor texts, we had noted the authors’ uses of figurative language. Students spent time collecting ideas of figurative language they could include in their writing. In Up North at the Cabin, Marcia Chall uses metaphors as she describes her cabin activities, which the students had especially enjoyed.

Feeling confident, the students eagerly began their writing. Their writing was truly a breathing of the heart. One student wrote about the time she spent at the hospital while her mother received a treatment they hoped would save her life.

At the hospital, I count the familiar squares in the ceiling. I look around at the room, watching the medicine drip into my mother’s arm, hoping it will be the cure she needs. As the hours stretch on, I wander down the hall to the vending machine, staring through its windows for a treat.

One child had lost her grandmother in the fall and remembered visiting her house.

At grandmother’s house, I am an explorer, discovering new places and finding interesting old objects. As I walk through the familiar rooms, I think back to where these items are from. Looking at the dusty pictures, I travel back in time remembering past vacations with Grandma. As I go outside, I climb up the crumbling rockwall. I spend a moment not worrying about anything, just being a kid.

Happy times at a grandparent’s house was a familiar theme.

At my grandparents’ house, I am a detective searching for clues of sea life. Putting on my snorkeling gear, I am submerged in the great blue sea. Slowly moving my arms and flippers, I move through the water, gazing at the ocean floor. A school of fish suddenly surrounds me like ants on an ant hill.

This writing was a learning experience for both my students and myself. As students reflected on places that were significant in their lives, their writing helped me learn more about them. All of us were reminded that writing provides both the author and the reader an opportunity to connect on new levels. As I plan writing engagements for the next school year I will continue to look for ways that my students and I can use writing as a way to connect emotionally, helping us both recognize and manage our emotions.

Lesson Adaptation for Primary Students

The lesson can be adapted for primary students. First, ask students what everyday places are special or important to them. Where are some places they like to go? Gather their ideas on chart paper. As students share ideas, encourage them to be specific in their places.

Read the book All the Places to Love aloud to the class. As you read the book, collect the places that were special to the boy and his family. Point out the phrase “Where else can . . . “ that is repeated after each place. What is meant by these words? Why might the author have used this phrase?

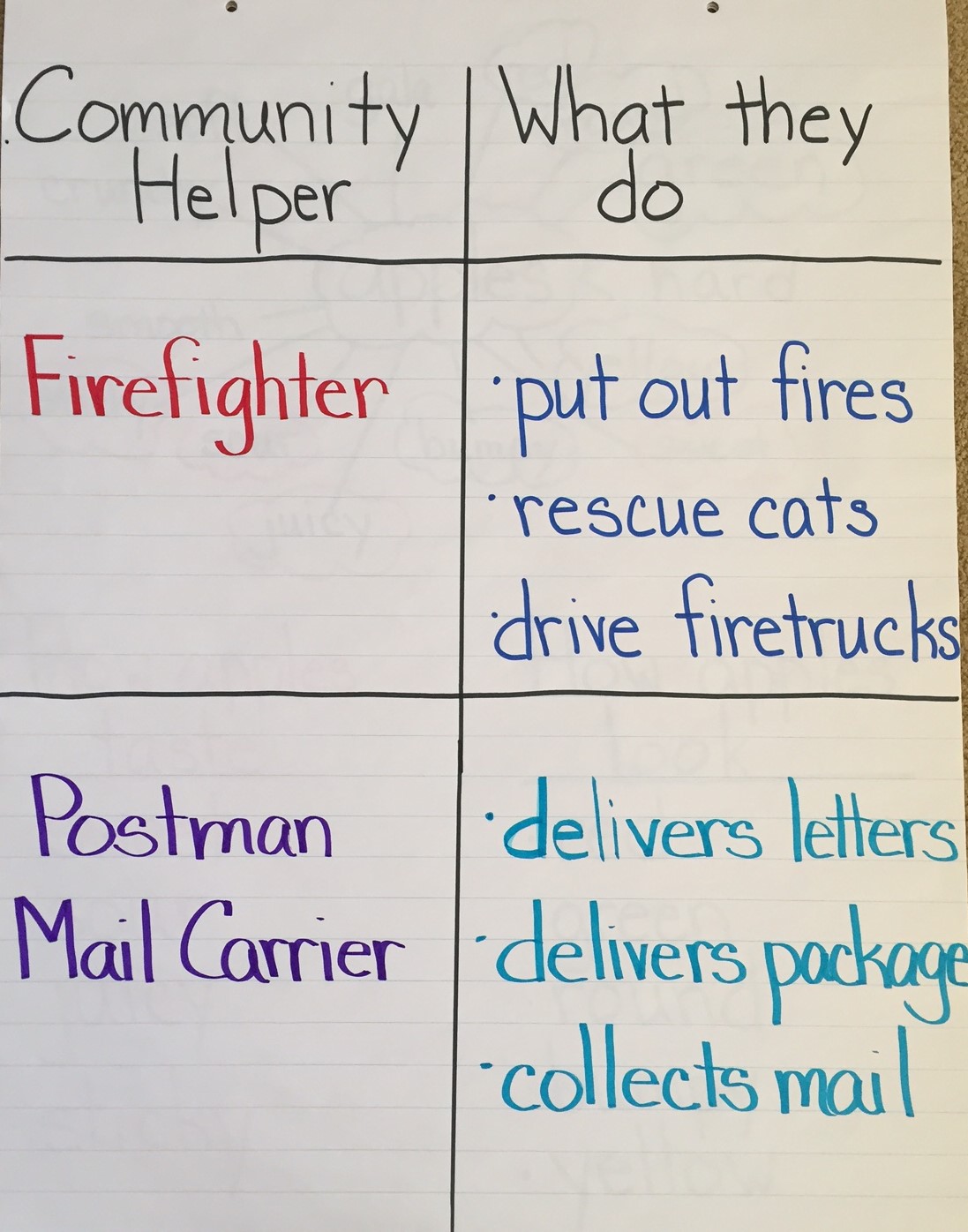

Return to the collection of special places. Students will brainstorm activities they do in each of these places. What do they enjoy doing at the park or at the library? List these activities next to the places.

Provide students drawing / writing paper. Using the chart as a reference, students can choose a favorite place. On the top of the paper, students will draw the place they have chosen. Provide time for students to include details in their drawings.

Students will now write about their favorite place. For example: One of my favorite places is the arcade. After they have identified their place, students will complete the sentence stem: Where else can . . . For example: One of my favorite places is the arcade. Where else can you play games for just a nickel? Where else can you find games for the whole family?

Students can create a book about their favorite places.