Hiking in Colorado’s rapidly changing mountain weather teaches hikers the importance of taking essential equipment. While carrying any more weight than necessary is not appealing, neither is being stuck on a mountainside without the necessary supplies. On a recent hike, we experienced sunshine and 80-degree weather, along with snow flurries and a 20 mile per hour wind. I was very thankful to have thrown in my essential headband and mittens for the cold weather.

Teachers have always been essential workers – but this has never been truer than this school year. Flexibility, always a teacher requirement, is more important than ever. Teachers are teaching in person, in a hybrid format, or totally online. Routines and schedules that were part of the school day of the past have been shattered. Time, always a precious classroom commodity, is now being used for necessary safety protocols.

With all these demands on teachers and students, instruction goals have to be altered. With that in mind, teachers are focusing on essential lessons. What is essential in writing instruction?

Students need purposeful and targeted writing instruction. We do not want our students to continually practice bad habits. Assigning students questions to answer or paragraphs to write without providing them the necessary skills is detrimental to students and frustrating for teachers. The following are essential skills students must have to become successful writing.

· Recognizing, speaking and writing complete sentences.

We continually speak with 5th grade teachers who are concerned their students do not write in complete sentences. This foundational skill should be introduced at the beginning of every school year – from kindergarten through 5th grade.

Introduce students to the components of a complete sentence. In Write Now – Right Now, we call this concept Team Complete. Kindergarten students can learn to recognize complete sentences and orally respond in a complete sentence. Make speaking in complete sentences an expectation of your classroom, whether you are in person or meeting virtually.

Intermediate students need to review the components of a complete sentence. As with primary students, speaking in complete sentence should be a classroom expectation. Spending time practicing sentence fluency and word choice is essential at the start of the school year. Insisting on correct conventions at the start of the school year is essential. Encourage students to play with language, experiment with word choice and create interesting writing. When that is done, students will then double check their work for correct conventions. While this is a challenging process for teachers, it is well worth the time.

· Use planning tools prior to writing.

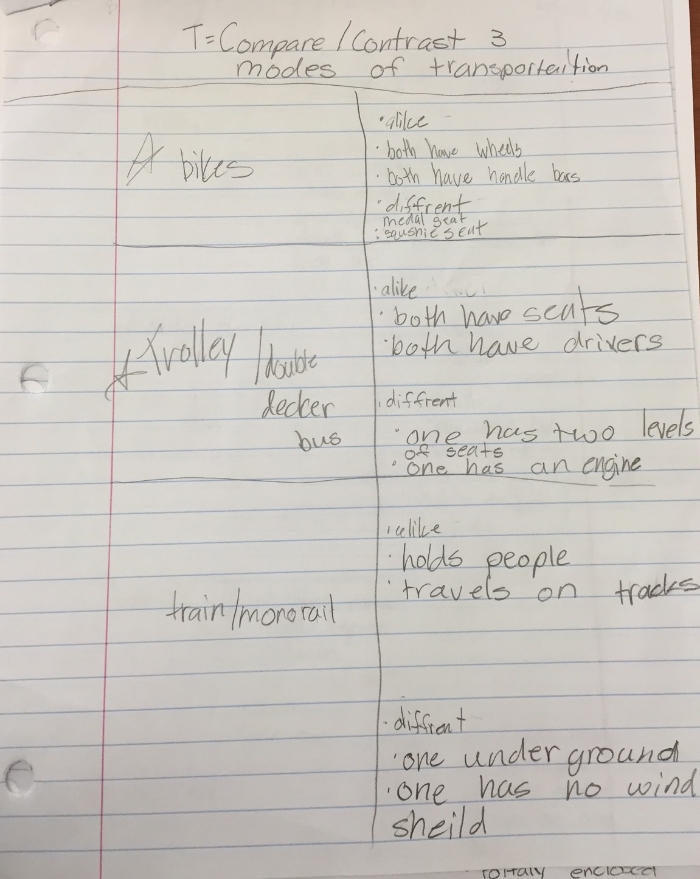

In the past, we often told students we write like we talk. This is not true, for our speaking is often random and spontaneous, jumping from topic to topic. Students’ writing will be significantly better if they are taught to organize their thoughts prior to writing. At Write Now – Right Now, we encourage teachers to use only one graphic organizer for all expository writing and a single organizer for narrative writing. Time is better spent teaching students how to use the plan effectively than spending time learning an array of plans. Students must know the difference between the terms: topic, big ideas and details. Teaching students how to add interesting and relevant details is a skill which leads to effective and interesting writing.

· Only assess what you are teaching.

It is difficult for all of us to let go of errors we see in students’ writing. However, grading will become less frustrating and more productive if you only assess what you have taught. If you are working on complete sentences, only assess that. Once students have mastered that skill, it can then be assessed in every piece of writing. Planning is an essential skill and can be assessed on its own. Writing is a process and each part of the process can be assessed separately.

· Give grace to both your students and yourself.

This year is not like other school years. You may not cover the same amount of curriculum and standards as in past years. Teaching schedules and requirements have changed. Provide grace for yourself and your students and celebrate your successes, big and small.

We are here to support you. Please reach out if we can be of service in any way.