Spend time with a toddler, and you will find yourself answering the question “Why?” dozens of times an hour. Spend time with teachers hearing about a new program or initiative to be introduced into their school, and you will hear the same question.

Understanding the why behind any change helps us both assess the relevancy of new ideas, form our own opinions, and determine the priority we will give to the initiative. One of the least understood areas of elementary standards falls under the area of writing. Research is helping educators understand the importance of teaching writing, the most effective ways to teach these skills, and the surprising benefits writing has on reading comprehension.

Why spend time teaching writing?

For information on research in writing, click here. http://www.writenow-rightnow.com/research

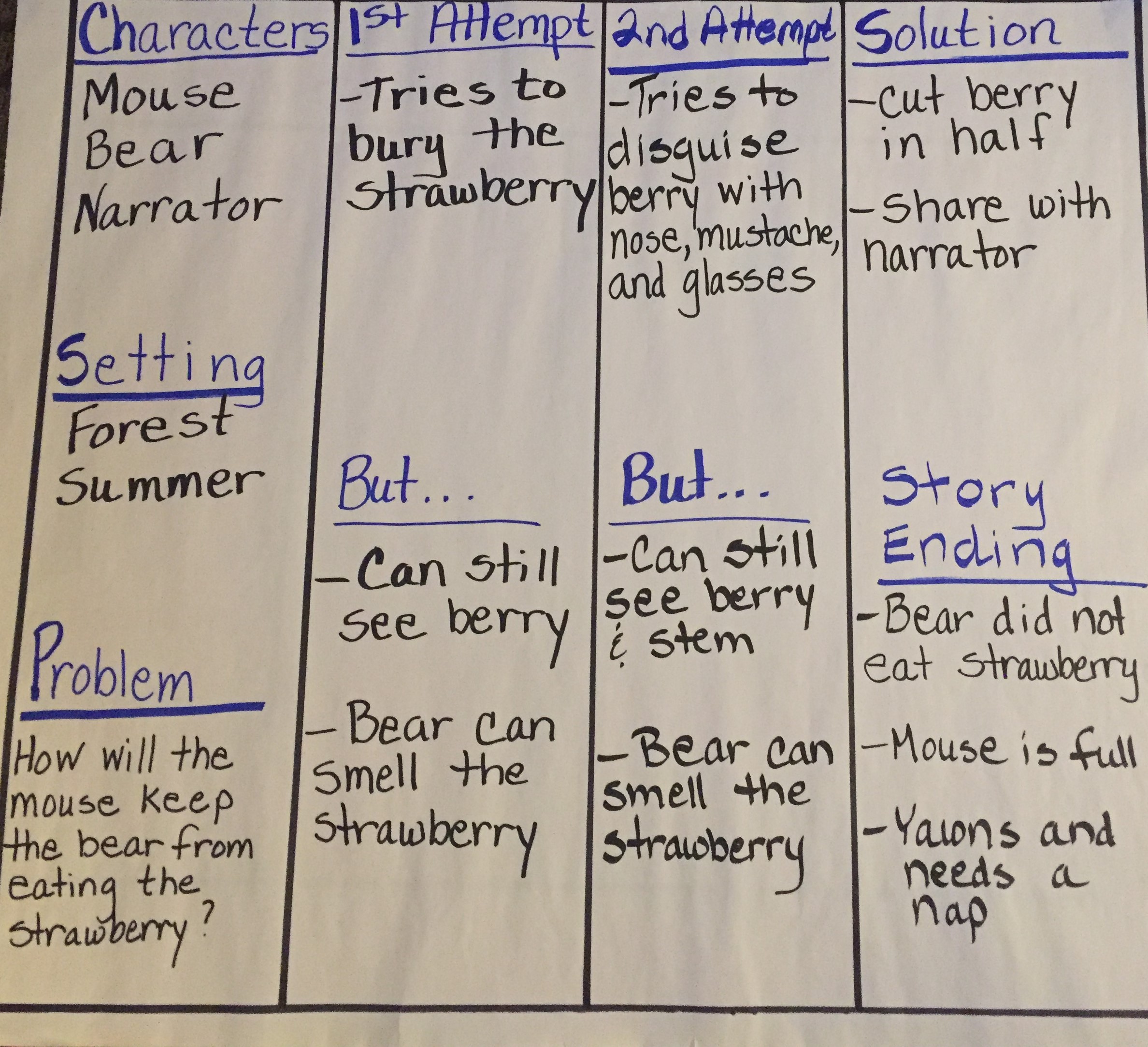

Teaching students to write does more than instructing students in composing an essay and writing a story. Writing about content material increases students’ comprehension, fosters deeper level thinking skills, and improves communication skills. Students’ literacy skills are improved when they are asked to write about what they have read.

Students must be able to communicate clearly. As we become increasingly more technology focused, the need for students to communicate their thoughts and ideas clearly is even more essential.

What is quality writing instruction?

Most students do not inherently know how to write well. Direct, strong instructional guidance is necessary for developing writers to recognize, practice and internalize the skills needed for effective and creative written communication. Writing is not just writing down what we say but is rather a form of communication that is extremely important in the work force.

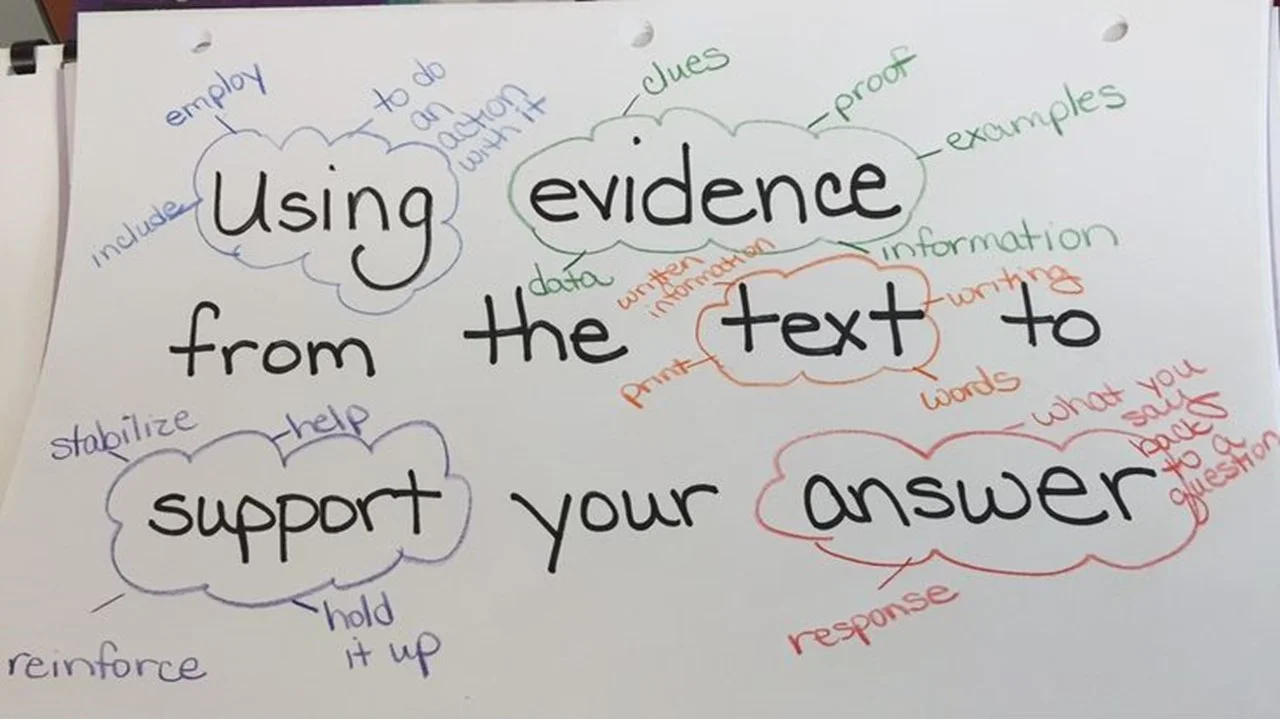

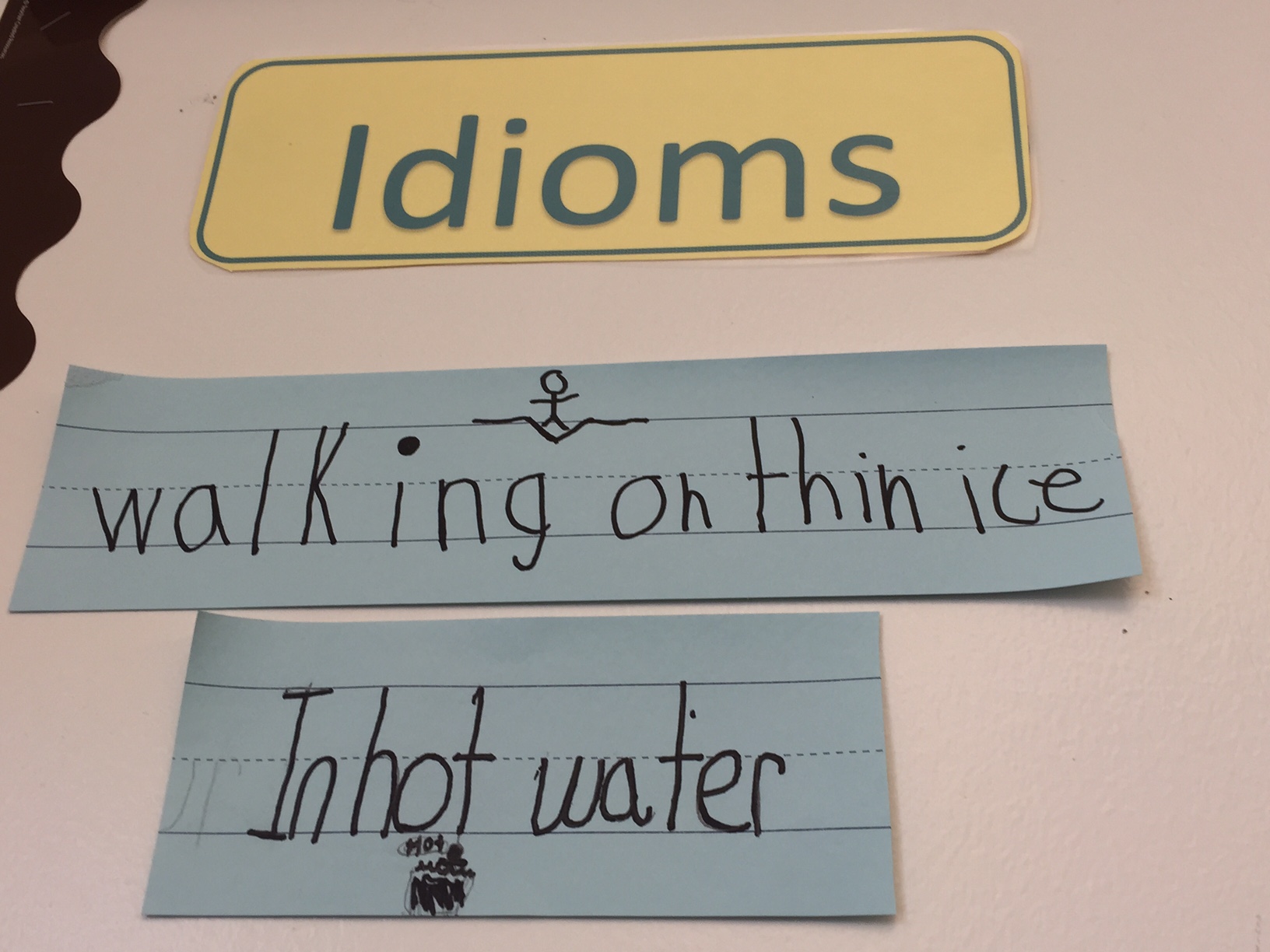

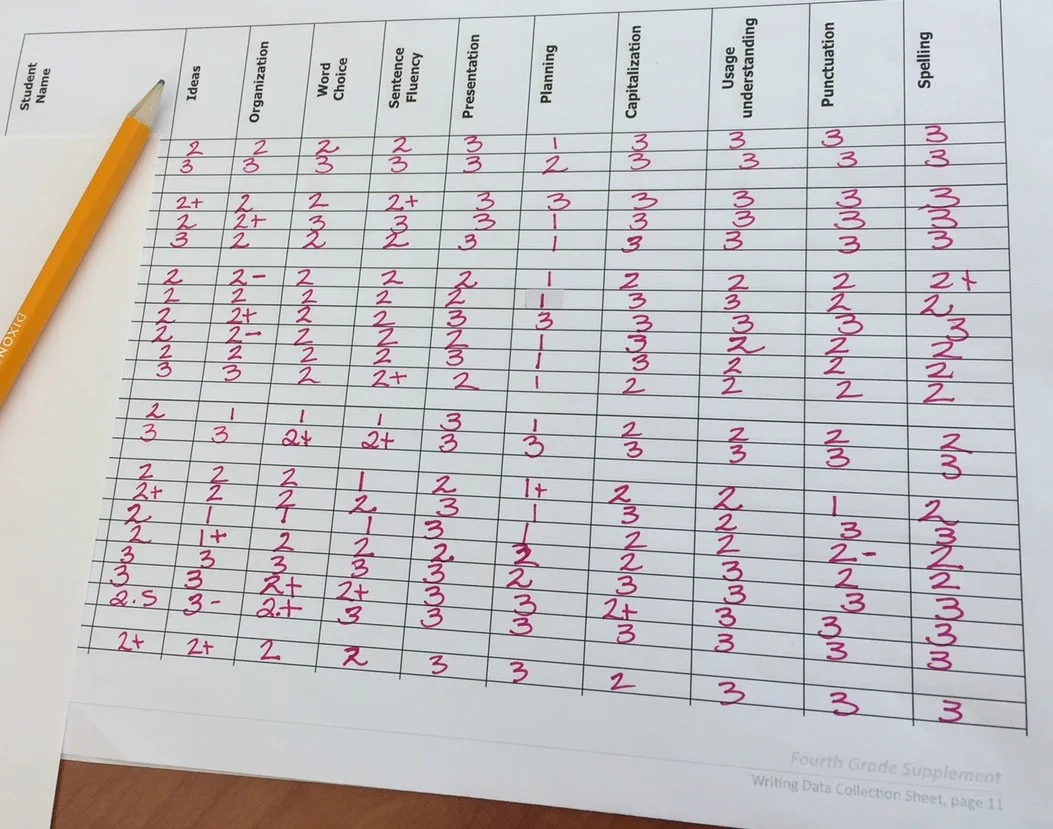

Writing skills must be taught explicitly. Before writing an essay, students must be able to both speak and write in complete sentences. Understanding the writing task, determining what needs to be learned from a text, and then taking the appropriate notes are all essential skills which need to be taught and practiced. Organizing any writing genre, from paragraphs, to essays, to narratives is a skill which benefits both the writer and the reader. Experts agree that asking students to write without proper instruction is one reason that writing scores across the country are so dismal.

Can writing instruction be engaging?

Students become excited about learning when their teachers are excited about teaching. The writing classroom should be interactive, with many opportunities for students to share and receive feedback. Instruction should be focused, with students engaged in practicing the taught skills. While practicing writing, students should be frequently encouraged to stop and listen to peers’ work, listening to quality writing and providing feedback. Teachers should be engaged with students during writing instruction, providing immediate feedback to students.

Writing is an essential component of literacy instruction. Thoughtful writing instruction must be a part of every elementary students’ school day. If we can help in any way, please reach out.

Happy Writing!