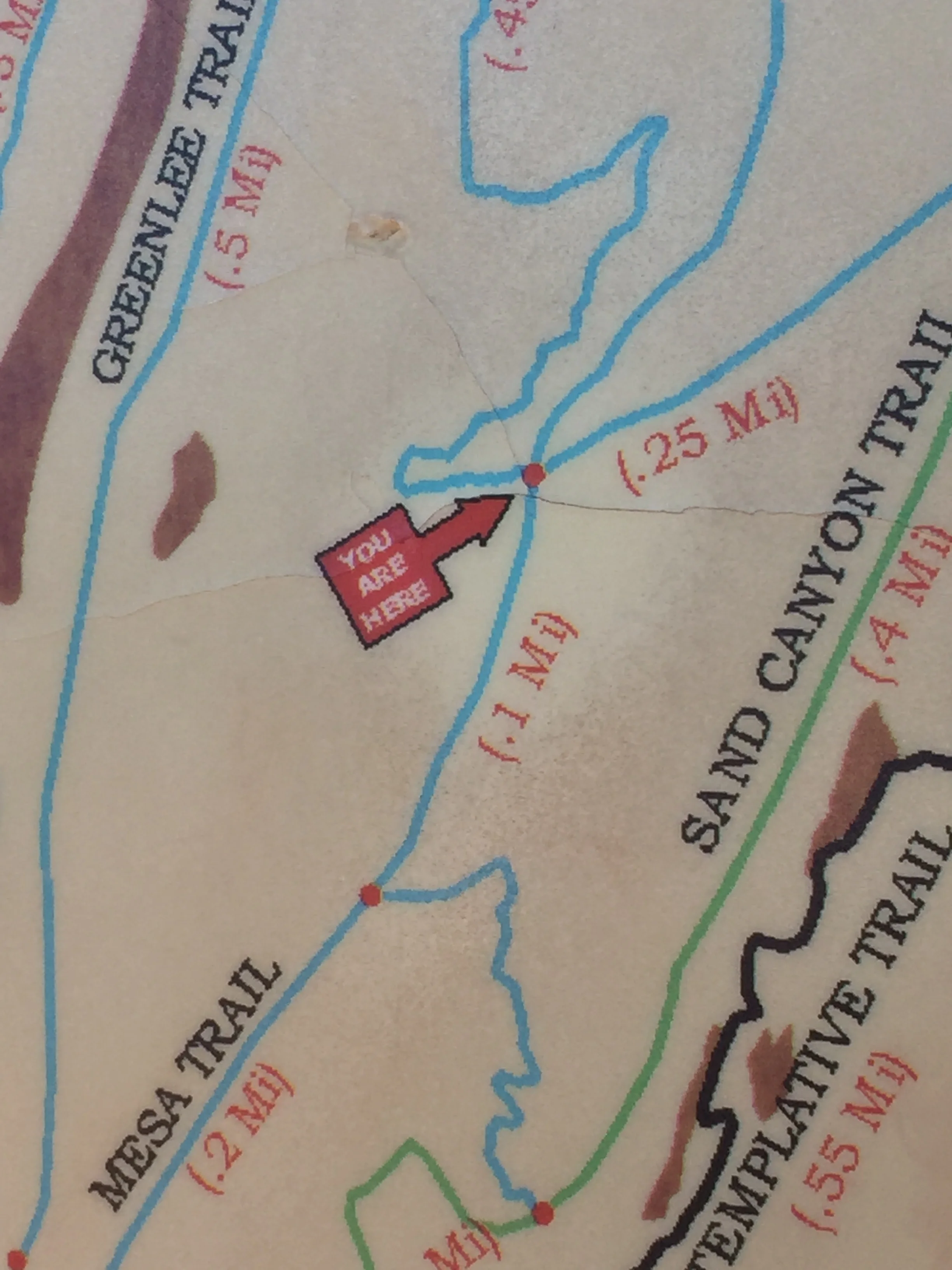

But some of us are! A sense of direction has never been a personal strength. Living in Colorado certainly helps – directions can be towards the mountains or away from the mountains. Yet, when it comes time to locate a new place, I use all the tools at my disposal. Car destinations are plotted on mapquest, using both the map and the step by step directions. When hiking, I stop at every posted sign, carefully following the arrows to complete the next turn! When using an old-fashioned paper map, I have to turn the map the direction I am facing to understand where I am and where I need to go.

Assessing Assessments

In the last few weeks, I have had two “away from school” interactions regarding the concept of assessments. The first experience came while visiting a new gym. Prior to taking the complimentary class, I was asked to fill out a goal and health assessment. The instructor said the information would be used to help me plan an appropriate exercise program and chart my progress as I attend classes.

A few days later I was with my 13-month old granddaughter at an ophthalmology appointment. After performing multiple tests, the doctor determined she needed glasses to strengthen one of her eyes. While making a two-month follow-up appointment, the doctor told us that we would check her progress based on the initial tests he had performed that day.

Teachers may find themselves overwhelmed with student assessments at the start of the school year. We, at Write Now – Right Now, are often asked if we recommend that teachers have their students complete a writing assessment at the beginning of the year. If you are debating this question, consider the following questions:

· Is a baseline, or beginning of the year, writing assessment a requirement at your school?

· Do you have a reason or plan for using the assessment results?

· Can you give the assessment in a reasonable amount of time?

The answers to these questions will help you answer the assessment question. The following are some tips to make a beginning of the year writing assessment positive for both you and your students.

Determine the assessment’s purpose

Why are you giving the assessment? Keep this purpose in mind through-out the process.

A Note to Kindergarten Teachers: You may choose to do the initial assessment when you believe your students are ready to begin writing instruction. Consider when the purpose of the assessment will be most appropriate.

Standardize the assessment

This is especially important if you are working with a grade level team. Prior to giving the assessment, choose a prompt for all students to follow, along with the time constraints provided. Use or develop a standardized grade-level rubric.

Write a prompt which provides students guidance in what to write

Do you want students to write an expository or narrative piece? We recommend providing an opinion prompt on a topic which students already know. In this way, you will be able to assess students’ writing, not their knowledge on a subject area. Include in the directions the number of big ideas or details students should provide in their writing.

Provide enough time for most students to complete the writing task

Teachers give pre-assessments as an indication of skills students already possess. In a writing assessment, it is not necessary for every student to complete the writing task. When time is up, simply collect students’ writing. It is helpful to note both students who rush to completion and those who will require extra time.

Record non-writing behaviors / trends

Do you have students who immediately break their pencil or go to the bathroom as soon you mention writing? Are there students who stare into space the entire writing time, “thinking about what to write about?” Do you have students who need constant feedback and reinforcement during the writing time?

Use the “piles” grading method

We recommend first reading each paper and then putting students’ initial writing samples in piles – Good Writing, Writing in Progress, and Need Extensive Help, or whatever category works for you. As you read students’ work, put the papers in one of these three piles. Remember, you are assessing writing using end of year writing standards. As these beginning of the year assessments are not used for a grade, this generalized assessment protocol will provide you with all the information you need.

Look for patterns

As you read students’ writing, do any patterns become evident? Do students use a similar plan? Are conventions an area of strength or concern? Are students excited or reluctant to write? Is student writing organized, did students stay on topic, etc?

Keep writing samples to show students later

We all need to see progress. Keep these initial writing samples to show students later in the year. We recommend showing them to students prior to a midyear writing assessment. It is encouraging for students to see where they have been and how far they have come as writers.

Teachers are busy people! Taking a moment to assess your assessments, making them relevant, useful and efficient is time well spent.

Cause: An Engaging Cause and Effect Lesson Effect: Students Engaged, Learning and No Papers to Grade!

I was recently in a 5th grade classroom where the students were just starting to delve into the concept of cause and effect. The focus of the lesson was to provide students with strategies to help them correctly identify cause and effect relationships in text. When asked what they already knew about this skill, students could explain that the two concepts were linked to one another, and that one action led to another.

To begin the lesson, students created a two-column chart. The left side of the chart was titled Cause and the right side of the chart was titled Effect. We then read the 5th graders the picture book If You Give a Cat a Cupcake by Laura Numeroff. https://www.amazon.com/You-Give-Cat-Cupcake-Books/dp/0060283246 Fifth graders love the opportunity to listen to picture books and they were enthralled with the story. While reading the book, I slowly moved around the room. As I was walking and reading, these older students were whipping around in their seats, following me with their eyes as they intently listened to the simple story.

We first read the book for the sheer enjoyment of listening to the story. During the second reading, the students and I were looking for cause and effect relationships. As we found a cause, we would write it on our chart, followed by the effect of this action. The students quickly noticed that the cause must come first, as it is the catalyst for the effect.

The next step was for students to create an anchor chart to keep in their Reading and Writing Folders. Completed with the students, this chart included the definition of cause and effect, examples, and key words they might find in the text when looking for cause and effect. When students are a part of creating an anchor chart, the information becomes relevant and useful to them.

Students then browsed other If you Give…books and created a second cause and effect chart independently. Students were engaged in their reading and thrilled to be able to find cause and effect relationships throughout the new books.

The classroom teacher and I wanted to complete a quick formative assessment to see who required extra support on this skill. Each student took a quarter sheet of paper and in the corner of one side wrote “Cause.” In the opposite corner, students wrote “Effect.” Students could choose to either write a Cause or Effect sentence in the appropriate corner. They then exchanged their paper with another student in the class, who wrote the relating sentence. For example: A student wrote: Cause: Tom Brady threw an interception in the last minute of the game. His partner then wrote Effect: Tom’s team lost the game to the Denver Broncos. Another student wrote: Effect: The vegetables in the garden were destroyed. His partner wrote: Cause: Grandpa forgot to lock the gate on the sheep pen.

Student partners shared their sentences. As they shared, their teacher took notes on only those students she felt needed extra instruction. The following day she planned to meet with those students during a small group instruction time. All students whose name she had not written down received a passing grade on this assignment. Within a 15 minute assessment period, the teacher had given every student an assessment and knew who needed additional support. More importantly, the students had personally interacted with the concept of Cause and Effect and solidified their learning through the creation of an anchor chart. The students had mastered a reading and writing concept and the teacher was not taking home a stack of papers to grade!

Step by Step, (or not giving in to “Get it done, Now!”)

Every class has its own personality. This is both a joy and a challenge of teaching. Organization and classroom management styles that work perfectly one year may prove ineffective the next year. I have been reminded of this truth during the current school year. To insure student engagement and success with this year’s students, I need to provide instruction which adds new skills in a heightened sequential manner. Definite strategies are needed to help students deepen their critical thinking skills.

For the past week, we have been studying the prehistoric people of Colorado. My goal was for students to make the connection: As prehistoric people moved from hunter/gatherers to farmers, they had time to build homes and improve their lives. I knew that this required higher level thinking skills and that students would need to follow specific steps in order to reach this understanding.

We began by setting up a chart where students could record their notes. The chart was divided into Dates, Homes, Food, Hunting/Farming and Additional Facts. As we studied each group of people, students completed the correct portion of the chart.

The students had acquired knowledge about these groups of people, but I now wanted them to draw some conclusions from this history lesson. What could we learn from these people outside of the facts of their existence?

Using chart paper, students drew pictures of the prehistoric people in chronological order. They illustrated the homes, food sources, weapons and tools used by each group of people. I was thrilled to watch students use ipads to discover ways to draw a kiva or an atlatl. Every student was engaged in drawing their chart and putting forth their best effort.

Now it was time to do some critical thinking. I introduced the phrase: “conclude or draw a conclusion,” which means to make a judgement based on evidence. Students studied each column in their chart and drew a conclusion. Student examples included: “Studying the prehistoric peoples’ homes, I can conclude that the people moved from living in caves and lean-tos, to building pueblos. When they lived in caves they moved from place to place. As they built homes, they stayed in one place.”

We repeated the same process for food sources and weapons / tools. Now it was time for the point of the lesson. What conclusion could students draw on how each aspect of these people’s lives impacted other areas? I was thrilled as I listened to students draw this important connection!

As a culminating activity, students were able to share their learning using a photo and voice recording program. (I gave my students a choice between Adobe Spark or Explain Everything.) As they had already given their conclusions deep thought and had written their responses, this final step was seamless and enjoyable!

The point of this learning engagement was not only for students to learn about Colorado’s ancient people, but to also deepen their critical thinking skills. In addition to the content, the goal was for students to learn how to learn, to learn how to document their learning, and most importantly, how to draw a conclusion and share their thinking with others. Slowing down and going step by step had worked well for all of us.

Teaching 2nd Graders to Read a Prompt!

I spent this afternoon in a 2nd grade classroom and was overjoyed to watch what those students can do! I had been working on reading and dissecting challenging prompts with the older students and I was curious to learn what the younger "little people" might do with the same task.

We gave each student the following prompt: Today you will be reading an article titled "All About Seuss." In the article you will learn many things about Dr. Seuss. Write an essay that explains how he got his name, one of the books he wrote, and how we honor him. Remember to use evidence from the text to support your writing.

Students were asked to read the prompt and locate the format that was required. They quickly understood that format was how we present our information and circled the words "write an essay" in the prompt. Next, we asked the 2nd graders to locate the topic of the prompt. They are well aware that the topic is what their writing will be about. A square was placed around the words "learn many things about Dr. Seuss." Now it was time to find the big ideas. There are three! Students underlined the following three phrases - how he got his name, one of the books he wrote, and how we honor him. Wow! We were ready to create a plan!

It was amazingly easy for these young students to transfer the important information from the prompt to a plan. The practice they have been provided in making plans was very evident. They are now ready to read the article with a clear purpose in mind. Tomorrow's lesson will focus on reading the text and finding details to complete the plan. I can't wait to see what they'll accomplish!

Do what you love – Love what you do — Life Is Good Motto

While waiting for a flight last weekend, I spent time in the airport Life is Good store. I must confess – I really love their merchandise. The shelves were packed with t-shirts, sweatshirts and coffee mugs depicting icons of recreational activities and the phrase “Life is Good.” I was tempted to purchase the sweatshirt depicting a travel trailer, a bicycle and a kayak, three of my favorite things.

Flying home, I was remembering this store. Every t-shirt graphic displayed a picture of some type of hobby – from fishing to enjoying a cup of coffee. Not a single picture had anything to do with work. There were no graphics of computer screens, classrooms, meeting rooms, or spreadsheets. While I understand the purpose of the company, it has made me think about the atmosphere of our classrooms. Do we approach learning with a “Do what you love – love what you do” attitude?

Meeting Our Students' Needs

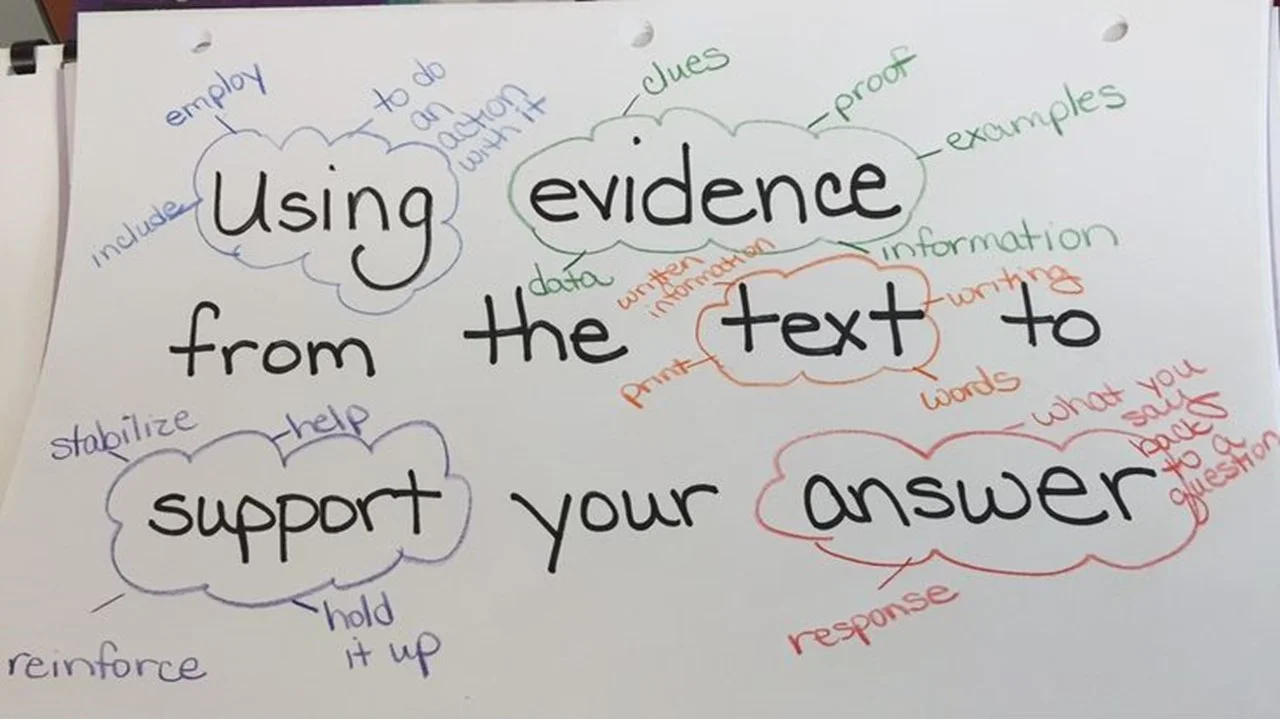

Our students come in all shapes, sizes and abilities. As teachers, we are constantly searching for ways to meet each of their educational needs. Sometimes we have a well thought out plan, while at other times meeting our students’ needs happens spontaneously. The latter happened in one of the classes that I spend time co-teaching reading and writing skills to 4th graders. We had been teaching our students how to find evidence in text to help support their answers. We first spent time just learning how to find evidence in the text before we had our students start answering questions. We then modeled and practiced writing a “Shining Star Answer” using the proof from the text. One of our struggling students needed additional work on putting these two skills together.

The Unplanned Teachable Moments

Many of us are asked to use curriculum maps to help us plan our instruction. While these maps are useful and at times essential, we must also remember to watch for those teachable moments which bring learning alive to our students.

During the first weeks of school, we were reading aloud the novel Fish In A Tree, by Linda Mulhally Hunt. Ally, the main character, is told she is “crossing the line,” and realizes her teacher is not discussing the finish line of a race. As we talked about this idiom, one student commented that his mom tells him he is “on thin ice” when he is in trouble. Another girl piped up that her parents tell her she is “in hot water.” A lively debate started over the use of water in both idioms – one water freezing and the other heated!

Data Information and Heart Knowledge

“Is it worth the time it takes?”

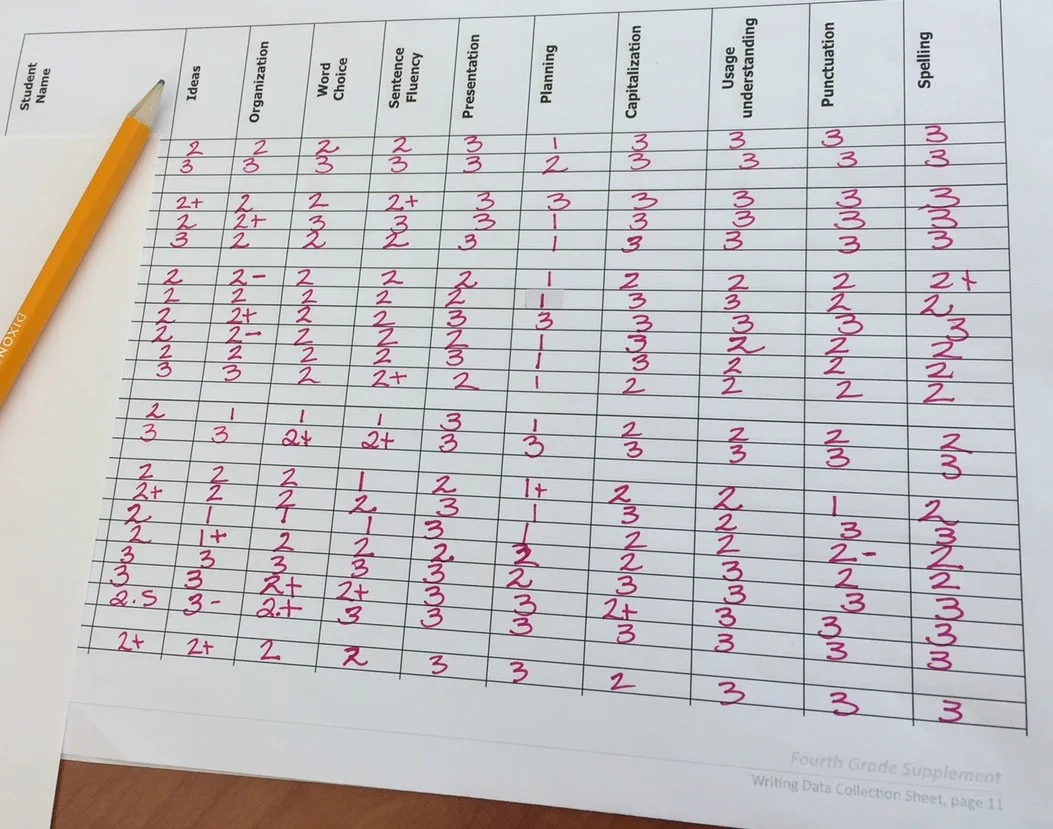

My teammates and I have vowed to start each planning meeting asking that question. As we look at all the standards we have to teach, the assessments we’re asked to give, and the learning engagements we want to share, we quickly run out of hours in the school day. The question was central in our discussion on whether or not to give a writing assessment to our fourth graders the first week of school.

After much thought, I chose to ask my students to write to the prompt,

“In your opinion, what would be the best job to have as an adult?” Explain the reasons for your choice of career.

Starting the Year – “Well begun is half done.”

Last spring, our school district decided to do away with parents and students purchasing the necessary school supplies. Instead, the district would charge parents a supply fee and the supplies would be ordered by and delivered to the school. Three days before our annual “Meet the Teacher” night, my classroom was filled with boxes of paper, notebooks, crayons, pencils, and miscellaneous supplies needed to start the year.