“It always seems impossible until it is done.” Nelson Mandela

Don’t you love finishing a project? There is great satisfaction in the words, “We are done!” We all have the experience of a project we have put off for a variety of reasons. It’s often lack of time, concern about how to organize the task, or an insecurity in how we are going to accomplish the task that may keep us from even getting started. What a wonderful feeling when the task is completed and we get to say, “This is finished. Hooray!”

Yesterday at Write Now – Right Now, we had the opportunity to say those delightful words. When Write Now – Right Now was first created, our goal was to provide a teacher-friendly, student engaging program for grades K – 5. As we met with teachers, we were continually asked if we had a program for 6th graders. Many elementary schools contain 6th grade and writing instruction is an integral part of their curriculum. For over a year, we have been telling each other it was time to write a curriculum for this critical age. We had found a variety of reasons (excuses) for not completing this task. Finally, last winter, we decided it was time. After studying standards, talking with teachers, writing, revising, rewriting and finally publishing – 6th grade is here!

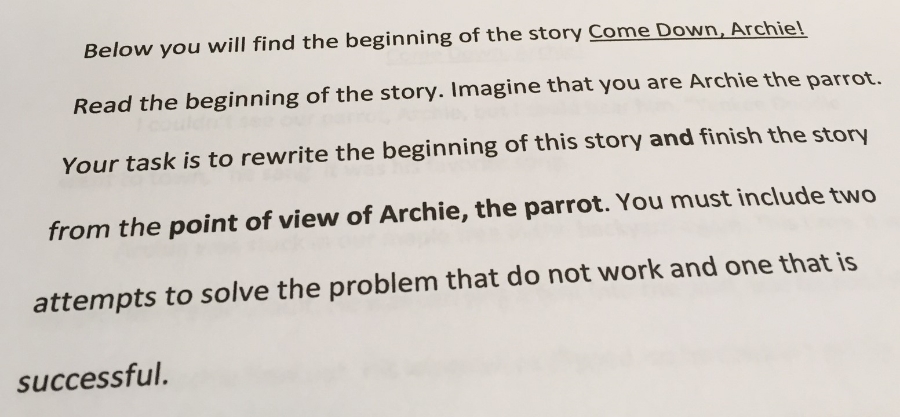

The experience has been a great reminder of how our own students approach a difficult task. What are some of their reasons for not beginning the task? How can we help them get past their insecurities and feelings of being overwhelmed? Just as importantly, how can we find ways to celebrate with them when they say “Hey, I finished this!”

We would love to know what you think. Visit our website to view samples of all grade levels and let us know what you think. http://writenow-rightnow.com

Happy Writing!

Darlene and Terry