“Well begun is halfway done.” My grandmother began many tasks with these words – from knitting a blanket to baking bread. Last week I heard these words come from my mouth as my fourth graders and I began to write the introductions to our narratives.

A story’s introduction is essential, as this is what hooks the reader, making them want to read more. There are five basic ways to begin a narrative. (Description of setting, description of character, problem, dialogue, and onomatopoeia) Instead of merely telling my students the names and types of introductions, I wanted them to discover these types for themselves. I decided to have them go on an “introduction search” and see if we could discover the five types together.

The directions were simple – find a fictional book and copy the first two or three lines from the book on a notecard. They could use any book as long as it was a narrative. Students eagerly jumped into the task, searching for their favorite book to use as their introduction sample.

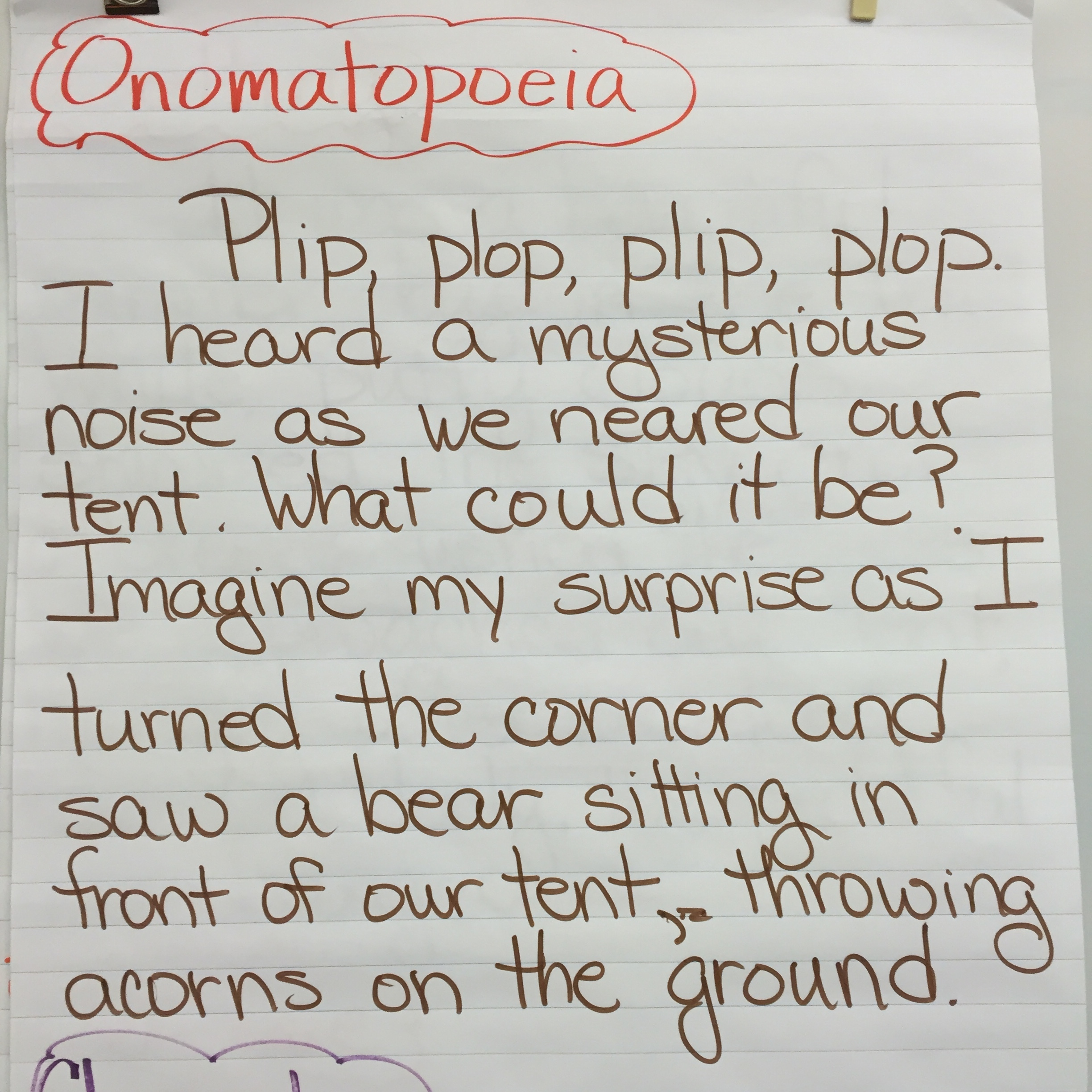

Now it was time to share what they had written and determine if we could find any way to classify or group these introductions. I was curious to learn if students’ samples included all five types of introductions. Students read their introductions one by one to the group. After they read, we discussed what was happening in the author’s words. Setting and dialogue were the first two we discovered. As we continued, examples of characters, problems and onomatopoeia also emerged. The student samples were taped on our introduction chart under the correct name.

The students were thrilled with their discoveries. Their learning was so much more powerful as they had discovered the categories on their own! It was now time to put what we had learned about introductions to use!

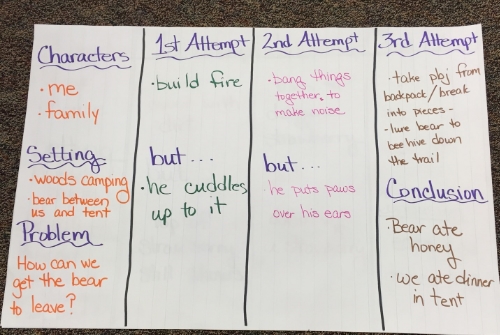

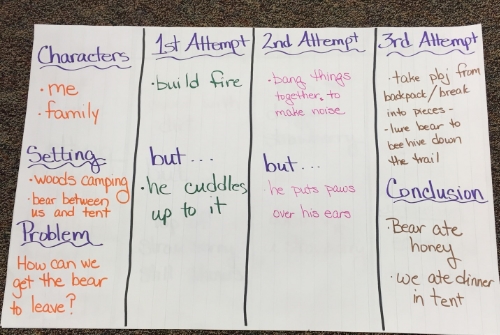

Previously, we had written a plan which focused on a family camping who come back to discover a bear was sitting between them and their tent. Using the same problem, the students had brainstormed their own solutions to the problem. We used this plan to write our individual introductions.

We began with Setting. After reading the examples we had collected, students were able to independently write their own setting introductions. We then moved on to dialogue and their favorite, onomatopoeia. The students were so excited to try out these new ways to introduce their narratives. Along with writing wonderful introductions, the students were also practicing putting details in their writing – a positive side effect.